|

Recently I’ve gotten good news from a number of artists. One just heard that their proposal was accepted for a solo museum show, another found new gallery representation, and another was excited to receive a much-needed grant. In each case their success came after a long effort, but felt like a miracle.

I am reminded of an ancient Chinese proverb: “He who would believe in miracles, will have to learn to wait.” I like this sentiment because it conveys a deep truth in the lives of artists. When success finally comes, it feels like a miracle, yet it is actually the result of a long effort. Real progress is always incremental, with many small steps that seem to lead nowhere until something good happens. But how do you stay on the path long enough to succeed? Most artists are good at blaming themselves for “failures” or lack of quick results, but forget to reward themselves for the daily effort and commitment it takes to make progress in an art career. Psychologists call this process “successive approximations.” Reaching a goal is the result of many tries, the theory goes, and it’s important to acknowledge and reward each attempt, even if it doesn’t immediately produce a result. The artist who finally found new gallery representation had taken dozens of such steps: visiting galleries, going to art fairs to see what is being shown, keeping their own work alive and visible in multiple venues. And then the new gallery found her, as they like to do. So remember to give yourself credit, celebrate every small thing you manage to do, every time you try, no matter what the result. In this way you create your own miracle. This week we celebrate our national independence day, in the midst of a divided country. Keith Haring’s 1988 image seems to capture our crazy reality. Since I have no wisdom on political matters, let’s consider what it means for an artist to be independent.

For some artists independence means making art while ignoring the marketplace, and finding other sources of income. If this strategy is satisfying to you, that is enough for now. For other artists independence means staying outside the increasingly troubled gallery system. You sell your art through personal channels, including a website and social media presence. If this is your approach, you might also consider art fairs designed for independent artists. Take a look at The Other Art Fair, which happens in Los Angeles, Dallas, and Brooklyn, and in various international locations. Another similar option is Superfine, now offered in San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C. Both fairs are juried venues modeled on the traditional art fair, but with a twist: artists present their own work directly, rather than through galleries. Think carefully before choosing this route, since independent art fairs cost money and time, and you need to be comfortable selling your work directly to the public. Read the reviews from artists who have done well (or poorly) at such fairs, and ideally attend as a visitor before you commit. Be sure to check out the quality of the art. But real independence might also mean staying focused on your art practice, day after day, developing your skill and believing in your vision, no matter how quickly or slowly you are able to make your dreams come true. How do you want to define your independence as an artist? Most of us get overwhelmed when we ignore an accumulation of small problems that hardly matter until they pile up and crash us down. These little things never get our attention in the midst of a real personal or global crisis, yet they eat away at the fabric of our lives, robbing us of energy and focus.

Take my garage door remote, for example. It sometimes worked and sometimes didn’t. It was a tiny issue, but in my life it became a daily annoyance. So, after many false starts, I found a woman who has spent the last 30 years in the garage door business. She pulled the thing apart and fixed it, charging me five dollars. Suddenly I had the bandwidth and momentum to tackle bigger challenges, because this little one was solved. So my advice to you is to identify some small thing that bothers you every day, taking your focus away from your art practice. Then take the problem out of the short circuit in your brain and get it into the hands of an expert. Just don’t give up until you’ve found a solution. Sometimes your problem is embedded in a larger system (most technical problems are). If you can’t find an expert, try a google search, starting with “how to fix . . . .” Look for a simple, step-by-step answer, follow the steps, and don’t give up until your problem is solved. By solving small problems, one at a time, you create a new mindset: problems have solutions, and you are capable of finding them. When you reach out to other people, and other resources, you realize that you don’t always have to go it alone. A 1945 Leonora Carrington painting just sold at Sotheby’s for $28.5 million. That fact raises an important question: is it time to rethink the prices for your art?

Record-breaking sales like this happen when an artist has entered the canon and collectors decide to make an investment, speculating that the value will go even higher. Most artists will not reach these dizzying heights, but the idea of placing value on your work is a critical first step in establishing your prices. An emerging or mid-career artist can think about value by paying attention to the time, effort, and talent needed to create each work of art. If you want to test this theory, do the math. Begin to track the time and effort you spend on a new work of art. Start with noting when the idea first appears in your mind, and then add up the time spent doing research, experimenting with materials or processes, in addition to the hours creating the work itself. If you’ve spent 40 hours on a painting, and are charging $400 for it, you’re earning $10.00 an hour. Is that a living wage? Next, your prices need to reflect the market you’re in. An emerging artist should study their local art market carefully. Visit galleries and nonprofit art spaces in your city, and note the range of prices charged by other artists making work similar to your own. Finally, your prices should reflect your own reputation and achievements. The auction prices for famous artists are high because they’re already famous. If you’ve been in a few group shows, but never had a solo show, keep your prices at the lower end of the range in your market. As you build your career you’ll be able to gradually raise your prices. The names alone are seductive: Guggenheim, Fulbright, MacDowell . . . their siren songs call to you. These big fellowships offer the promise of significant time and money to support your art practice. How do you decide if you should apply?

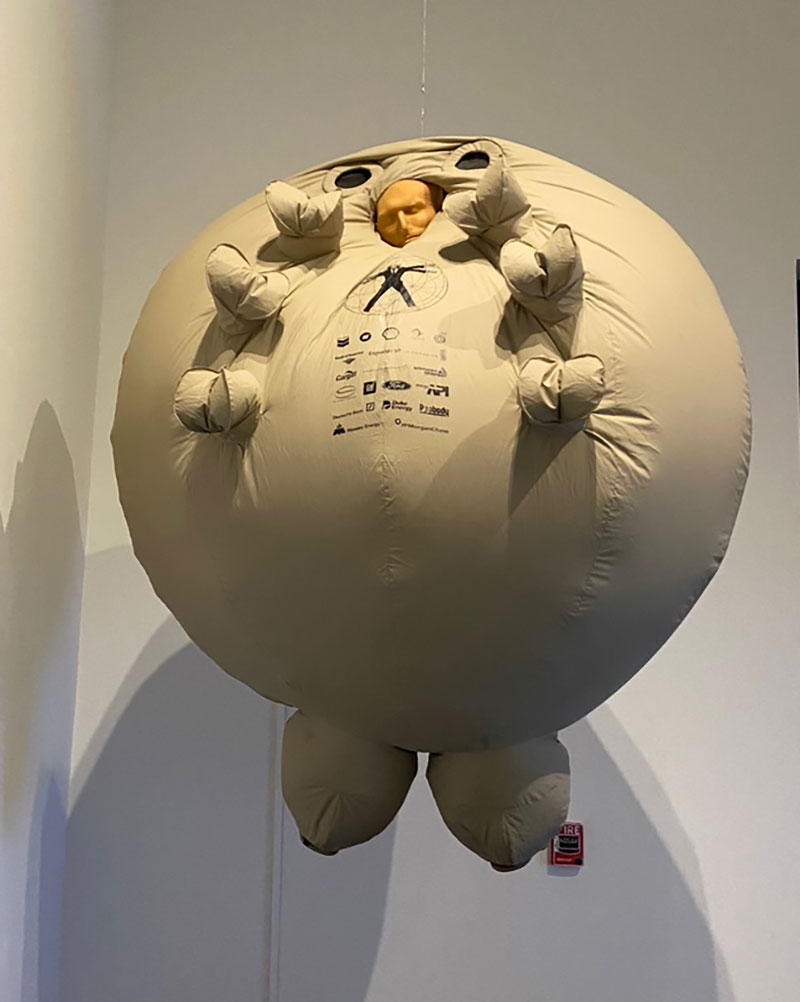

Such fellowships often go to people who have already made it on the national scene. So before you jump in, review the past winners. Don’t just look at their work, assess their careers. Find their CV or resume, and examine four areas: previous grants received, solo exhibitions at museums and universities, artist residencies attended, and press reviews. Then compare your own accomplishments. If you think you have a chance, go for it! At least a month before the due date, dig deep into the application process. If they care about financial need, what documents will be required? Do they ask for a project, or do they fund your practice overall? Leave yourself plenty of time to complete the application, and get help with the writing if you need it. Most of the big fellowships ask you to describe the scope, intention, and impact of your art. This is a difficult and valuable process, where you step outside your art practice and explain it to others. Even if you don’t get chosen this year, such work is never wasted. You’ll generate documents to revise and use again. If your research tells you that you don’t yet have what’s expected for the national fellowships, don’t be discouraged. There are many state, local, and regional opportunities out there. And by understanding where you need to strengthen your own resume, you’ll be able to focus your efforts so that you’ll be at the top of the list next time. As you may know, the latest Whitney Biennial has just opened in New York, greeted with the usual mixture of critical acclaim and complaint. If you’re not able to see the show in person, take a look online. The theme is topical, as the title suggests. “Even Better Than the Real Thing” explores the question of what is real in the age of artificial intelligence and the fluidity of identity.

What caught my eye this time was not so much the show itself, but the background of the artists. Hyperallergic, the Brooklyn-based online journal, has compiled new statistics that confirm the geographical bias of this prestigious exhibition. Over forty percent of the artists are based in New York or Los Angeles, and all but 10 (out of 71) live in coastal states. What does this mean? Is the best art being made only on the two coasts? Absolutely not. Remarkable art is created everywhere, as you can see in regional museums and galleries and artist studios across the country. The geographical focus of the Whitney Biennial just reminds us that webs of connection in major cities create networks that launch artists. Yet when we dig deeper into the backgrounds of these artists we find that they grew their careers in smaller venues across the country. Nobody begins with a solo show at MOMA. For example, Takako Yamaguchi’s first exhibitions were at the Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, the Museum of Art in San Jose, and the Nevada Museum in Reno, a long path that led her to be selected for the Whitney Biennial. This one example, among many, illustrates the point: America grows its artists. The country provides multiple venues where any artist can begin the process of launching a career. What’s your next step? Most of us realize that the art world has gone digital. It began during the pandemic and the trend has grown. This is not entirely a bad thing, as new online options for selling art can be a real benefit to artists who don’t have access to galleries. Online sales to collectors have also increased, with buyers “visiting” art fairs digitally and purchasing art directly from the galleries showing there. These sales figures are surprisingly high.

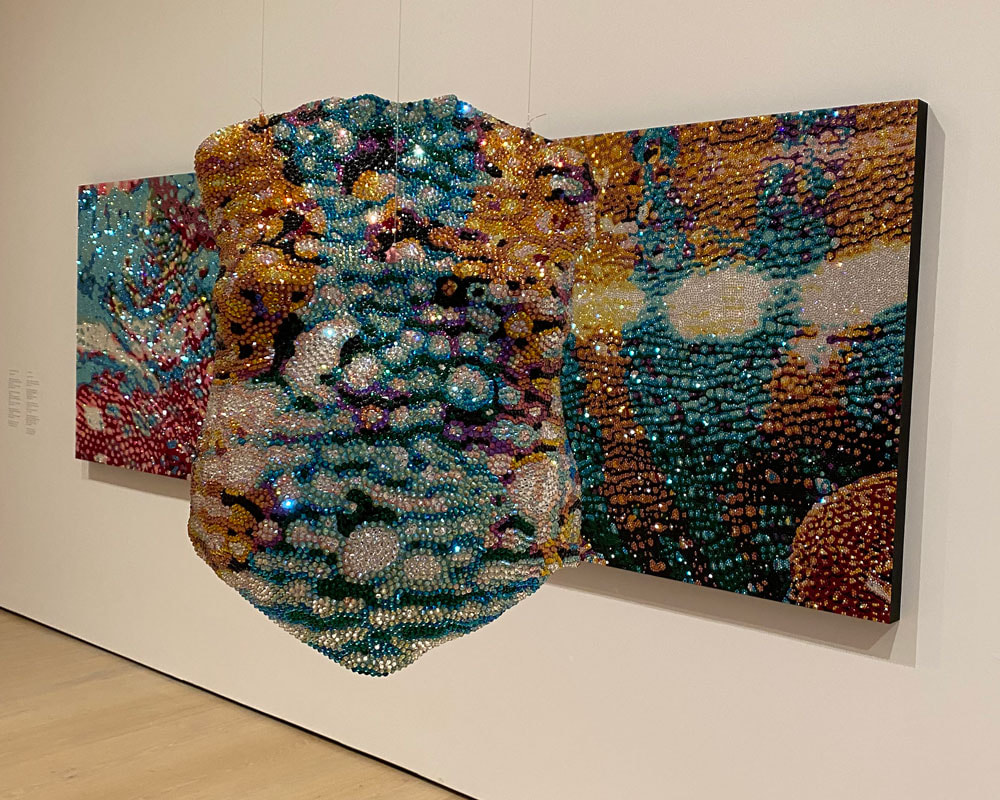

Yet I’m seeing the downside of this trend everywhere. The digital world has replaced the human in most of our everyday lives. Your car runs by computer, and gives you (sometimes welcome) advice about your driving. When you need to solve a problem, a “virtual assistant” replaces the human voice you were expecting. Most of these changes have an upside, and we all adapt as best we can. For artists, the impact of the digital experience is not well understood. Many artists find themselves overwhelmed by the technical demands of an art career, and end up feeling alienated from the fundamental process of making art. The two experiences are nearly opposite. Art making is messy, experimental, rough, unpredictable, just like real life. The digital demands of an art career require a logical, linear, step-by-step approach. Just think about what it takes to enter your work on Café or EntryThingy, and you’ll understand the difference. You need to push back against the digital trend. I believe it is possible, and necessary, to bring your creative self back into your art career. Thinker bigger, experiment, try new venues, talk to people, get off those screens and get out into the real world. I’m still thinking about the myths that get in the way when you’re trying to shape your career as an artist. Perhaps the biggest fiction is that you cannot combine a successful career with an authentic creative life. This illusion is alive and well on social media. People create ideal versions of themselves in order to seem more successful, more confident, more one-dimensional than they are. These avatars make the rest of us feel inadequate, as we live through our ordinary ups and downs, our doubts and fears. Many artists believe they have to be constantly upbeat in order to attract interest, despite the fact that their art grows out of their raw and messy, genuine selves. This illusion of the ideal self leads to another fiction. Artists believe that there is a secret “right way” to succeed, and in order to find it you have to apply for every opportunity you hear about, whether or not it’s right for you. This syndrome, sometimes known as FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), is emotionally exhausting, since you set yourself up for rejection and discouragement. Don’t chase random opportunities. Most of them are not worth your time and effort. It makes more sense to figure out your goals for the next year or so, and create a strategy to reach them. The best paths to follow grow organically out of your art, your values, and where you are in your career. Do experiment and try new things, but choose those that fit your goals. When you let go of illusions you discover a more complex and vital reality, where you will thrive. You don’t have to let go of your real self in order to succeed. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards The image you see here is from a remarkable exhibition I recently saw at the Boca Raton Museum of Art, called “Smoke & Mirrors: Magical Thinking in Contemporary Art.” While the exhibition’s focus was on stage magic and hoaxes perpetrated for financial or political gain, it made me think of the mix of illusion and reality in artists’ careers. One of the most seductive illusions is that the art world is a meritocracy, with only the best artists achieving recognition and reward. This belief makes artists doubt the value of their work, when what they actually need to improve is the quality of their relationships with people who can help them advance. Another illusion is that the art world is totally random in its functioning, that artists get discovered through sheer luck. We know that art careers don’t happen in a linear way, yet success isn’t random or accidental. It begins with a clear understanding of where you are on your path. For example, an emerging artist’s job is to become visible in a variety of venues, gaining experience and exposure. A mid-career artist uses that visibility to build a network of relationships, since opportunities come from people who know you and like your work. An established artist might focus on moving from local gallery representation to finding a gallery with a national reach. Yet your own values are the bedrock of your reality. Think about your life as a whole, and try to create the life you want to lead. While letting go of illusions will bring you clarity, a full creative life can bring joy and satisfaction. There’s real magic in that. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards The coming of January 2024 makes me think about New Year’s Resolutions. They hold the promise that we can shape our lives by declaring our intentions, and then writing them down. Whether this is true and useful, or just a happy fiction, it’s worth knowing how to make an effective resolution. First, I believe the best resolutions are long-term and big picture, focused on how you want to develop your life and art practice. Effective resolutions shape your behavior. While many think that goals should be focused on specific outcomes, it seems to me that the complexity and chaos of the art world make such planning a lesson in frustration. But when we think on a larger scale, the resulting actions can shape our future. A good resolution guides your thoughts and actions, helping you develop new habits. One of my favorites for creative people is: “become more visible.” This vow might lead you to attend an art exhibition in a nearby city, or to join a critique group, or become a member of a local nonprofit arts organization. Such a resolution makes you ask yourself, everyday, “how can I become more visible as an artist?” When resolutions are focused on process (rather than results), they open up new ways of approaching your life and work. One of the best, for creatives and the rest of us, is “discover new sources of inspiration.” Such a resolution puts you in motion. You explore the world around you with an open, positive mindset. My own New Year’s Resolution, both as a coach and friend, is simple: “talk less, listen longer.” What about you? Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Many of us get stuck when we’re launching our most important projects. Since your best work is often grounded in personal passion, you can feel vulnerable and confused about how to move forward. What if you can’t get it right? How will you know when it’s finished? When is it time to get feedback? It’s important to understand what ideas need in order to grow. You don’t want to expose your work to feedback and criticism too soon, when the work isn’t quite ready. But what conditions can you set up in order to nurture this work so that it becomes stronger? Gardeners struggle with this question all the time. To grow seedlings, they often use a heating mat and fluorescent lights to protect and nurture these young plants. This happens with tiny humans as well, as incubators provide premature infants with a safe space to live as they develop. Your own early ideas also need light and warmth, time and attention, and a safe place to grow. Trust yourself to provide a kind of incubator that prevents the harsh eyes of the world from commenting until the work is strong enough to stand on its own. Most important, protect your work from your own doubts. Silence the voices in your head that can suppress an idea before it has had time to germinate. Remember your successes, all the times you have prevailed in difficult circumstances. Your belief in yourself is the light and warmth new work deserves. When the time is right, do reach out for feedback from people you trust. Ideally choose supporters who can be objective, who can listen as you share your best intentions. Good feedback helps your work grow, but only when you are ready. Happy Holidays! Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Marie Kondo has made a fortune by telling people how to declutter their homes, so that they get rid of anything that no longer “sparks joy.” This idea has inspired one of my favorite exercises for artists. Artists face a challenging paradox. While the creative process itself is dynamic and unpredictable, creative people need structure and order in order to make consistent progress. When you declutter your living space, you remove unnecessary belongings. It’s what we do (or intend to do) when we run out of closet space or move to a smaller apartment. When you apply this idea to your art practice, you open up mental space by finding time for what matters most to you. So here’s how it works. Examine two or three typical weeks in your calendar, where you write down appointments and other commitments. Notice how you actually spend your time, and look for patterns or recurring activities. Then think about your long-term goals, your highest priorities. How much time do you spend on them in a typical week? For example, many of us spend hours each day on administrative tasks, errands, and meetings. Such activities can become automatic, habits that drain your energy. Look at your own calendar, and ask yourself if any of your recurring activities could be eliminated. Then remake your calendar by blocking out chunks of time devoted to your most important goals. Mark these times as appointments, just as though you were going to the dentist or meeting a friend for lunch. When you think about accepting a new invitation, you’ll look at your calendar and see that you’re “already booked.” You have an appointment with yourself. For many artists this will mean finding the time to create the work that is the core of your practice. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards The Hammer Museum exhibition, Made in L.A., is still on my mind. I wanted to introduce another remarkable artist whose work both dazzles and makes us think. Young Joon Kwak (she/they) is a Korean American artist and performer, and is showcased in the exhibition’s section called “The Feminine Absurd.” This work caught my eye because it shows how the best conceptual art can also be visually stunning, even humorous in how it reveals its intentions. Kwak covers bodily forms with resin, glitter, and rhinestones, while inside she gives us glimpses of bodies floating in space. These paintings and sculptures reflect your own image as you move by, so that you cannot quite identify what you’re seeing. The artist’s work is about different ways of understanding queer and trans bodies, asking us to rethink how we look at bodies, to pause before we label them too quickly. Kwak’s art practice is also fascinating because it reveals how beginnings shape a career. Even artists who are now famous often start out in community venues rather than commercial galleries or museums. Young Joon Kwak first showed at Roxaboxen Exhibitions in Chicago, NP Contemporary Art Center in New York, and Commonwealth and Council in Los Angeles, all nonprofit or artist-run spaces. Such organizations provide support, community, and connection for artists struggling to make their voices heard. It’s not surprising that Kwak’s first publication was titled “Nothing Great Gets Done Alone.” So if you’re stuck, or looking for ways to get your own work seen, consider opportunities in nonprofit art spaces. Reach out to these community art venues, support other artists there, and find ways to collaborate. It seems to me that nothing gets done alone. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Last weekend I saw Made in L.A. at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Curated by Diana Nawi and Pablo Jose Ramirez, this remarkable exhibition brings together 39 artists and collectives now living and working in Los Angeles. This sixth version of the biennial is subtitled “Acts of Living,” from a statement by the artist Noah Purifoy: “One does not have to be a visual artist to utilize creative potential. Creativity can be an act of living, a way of life, and a formula for doing the right thing.” This expansive view of what constitutes art is echoed in the diversity of the artists presented. Not only are all genders and many ethnicities included, but for the first time the selected artists range in age from 26 to 83, with five artists over the age of 70. While you can read about the artists’ intentions through curators’ statements on the wall or in the catalog, their works speak to you directly, viscerally, making you smile or frown, or just stand in wonder at such unique and surprising ways of seeing the world. What does this exhibition say about what it means to be an artist? That your art can be embedded in your life, in your values and commitments and community. The exhibition showcases artists whose art grows out of their everyday lives. For example, Esteban Ramón Peréz, whose work in leather is highlighted above, learned the trade of upholstery in his father’s shop, and used his skills to combine textiles, sculpture, and abstract painting. Acts of Living honors 39 artists who have never given up, who have put all of themselves and all of their values into their art practice. That’s a powerful inspiration for all of us. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards I’ve recently had two experiences with AI. I’ve tried it as a Google-like search tool, and I’m seeing how artists are using AI to jumpstart their writing. Both are worth considering, but you need to proceed with caution. When you use an AI chatbot to ask just about any question, you’ll get what seems to be a thoughtful answer. The chatbot’s response comes in an instant, nicely packaged in short paragraphs, or even a list of steps. In contrast, when you use a search engine like Google, you have to sort and sift, and choose the answers that sound credible to you. It’s a messy process, but you learn as you go. The chatbot’s instant response is more efficient, certainly. But it creates the illusion that this is the truth, even though it’s just the result of a sophisticated algorithm looking for answers on the internet. Your own brain is left out of the process, since you’ve avoided the real research, where you struggle to refine and sharpen your inquiry. Artists are also using AI to help them write about their art, again with mixed results. Sometimes it will stimulate your own thinking process, give you new ideas and new language, or just jump start your own writing. But when you delegate the process of thinking about the meaning of your art, you can end up with a superficial statement that sounds good but says little. All creative work is a messy process of discovery, experiment, risk and reward, a long path toward finding your own voice. When I asked my chatbot about the creative process, it actually agreed with me: “it is essential to remain open to inspiration and exploration throughout the creative journey.” Go figure. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Recently I upgraded my TV to a “smart” one, thinking it was yet again time to embrace new technology. It was supposed to make my life simpler, as the TV could do all kinds of things it thought I needed. Alas, weeks have passed and I’m now realizing that my TV, like most such devices, speaks a language I have to learn. This seems to me also true for artists trying to keep up with an art world that has gone digital. Let’s first remember why technology is so challenging for many artists. Creative people perceive the world primarily through the senses. You are visual and tactile, you need to see and touch in order to understand. Yet so many aspects of technology are invisible. Since you cannot get inside your devices to see how they work, you have to learn their language. Yet that language can be confusing! Many technical terms, like function or format or interface, are abstract, and others are familiar but actually have a different meaning (like my personal favorite, “cookies”). When you don’t know what technology terms mean, you cannot master technical tasks. You have to speak the language. So that’s where you start. If you don’t know how to do a technical task, begin by defining terms. Using Google or another search engine, you might ask “what does it mean to embed an image in an email?” Find an answer written in clear language, with step-by-step instructions, so you can see the words that explain the process. Print out the instructions. Then do it yourself, several times, trying and failing until eventually you get it right. I’m going to talk to my Smart TV now. I think I understand what it’s saying. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards We’re in the middle of Summer, and many artists are struggling to find time for their art. Vacations, visitors, or just the pull of a beautiful day can distract you from the structure that holds an art practice together. Your own working schedule may be quite specific or fairly loose, but most creative people need some structure in order to be productive. Since you don’t get organized by going to a “regular” job every day, artists have to create their own container. But what happens when the demands of your life overwhelm your best intentions? Experienced artists know that the creative process has its own rhythms. They don’t panic when they veer off course, for whatever reason. But when you’re just starting out, you don’t quite trust yourself and can go into a downward spiral when you stop making art. Don’t judge yourself harshly if you need to take off a week or two. Keep in mind that you might still be working on your art even when you’re not in the studio. Your mind keeps going, and sometimes you find new ideas or solve creative dilemmas when you’re “not working.” Don’t try to be perfect. Holding yourself to an absolute standard of productivity doesn’t usually work for creative people. Instead, when you know the demands of your life might interfere with your regular schedule, plan ahead. Preserve a few minutes every day to imagine what you’ll work on when time allows. Sketch out an idea or make notes in a journal. Keep your intentions alive in your mind. The secret, of course, is to just begin again. A few breaks can even renew your spirit. Remember, you’re going to be an artist for a long time. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Sometimes events conspire to remind us that we don’t have unlimited time to do what matters most to us. An accident, an illness, even a celebration can hit us with the realization that time is finite and needs to be honored. While this truth can be startling, it can also lead to action. When time is short, we might decide to stop putting off difficult conversations or decisions. We might be ready to finally forgive someone, or thank someone, or just acknowledge a truth about ourselves. We might decide to tackle that impossible task that looms in the Land of Should. The hardest part is to figure out what matters most. For some it will be our families, or close relationships, or a cause we care about. Artists share all of these commitments, of course, but there is also the work to be done. Creative people struggle to find a way to express their vision. It’s a messy process, full of doubt and hope, failed experiments and happy surprises. Remember, just doing the work matters, but sharing that work with others is also important. You might not yet have found your place in the big art world, but you can still dedicate time each day to being, or becoming, an artist. The work you make may well last beyond your time. So, if time is short and seems to be going by too quickly, do what matters most to you. Do it now. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Rejection hurts. I’ve helped many artists “handle rejection,” but two recent rejections of my own reminded me of what it feels like when the door you were trying to open gets slammed in your face. One of my rejections was personal, the other professional. In both cases I had put forth my best effort, indeed my best self. For artists it’s always personal, because your art is part of you. In order to build your practice you’re always applying for things: juried shows, residencies, grants, awards, and each time you make yourself vulnerable. When rejection happens, you take a body blow. The places that hurt are real wounds, even if they don’t show. As I was figuring out how to handle my own rejections, I remembered my favorite advice from a therapist friend: there’s no way through it but through it, so feel your feelings. You might also reach out to your allies for support, and then start to put your suffering in a larger context. Think about what’s still positive in your life and work. Since rejection can place a dark filter over everything, try to remember what’s going well, what you’re good at and grateful for. This might include friends and family, your work, your talent, everything that remains true in spite of the powerful noise of the NO. Then step back, and see if there’s anything you can do, or anything you can learn from the experience of rejection. You might take a proactive approach, and get a second opinion, or just keep submitting what was rejected. You could join a critique group so that you get regular feedback from people you trust. Most of all, move on. One negative opinion does not define your work, or your worth. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards What would it mean to think of your art practice as a business? Does that idea make you cringe? Many artists believe a business mindset will turn them into an alien being, a steely-eyed accountant instead of a creative. Nothing could be further from the truth. When artists don’t have workable systems for handling the business side of art, they spend too much time on administrative tasks. You can develop business skills by using basic learning strategies. Identify what’s important to you, research to discover new information, practice, experiment, and find the solutions that work. Gradually you will free up more time and creative energy for your art practice. Begin with small steps, so that you concentrate on putting the fundamentals in place. Becoming more business-like is not a personality change but a new set of behaviors, things you do on a regular basis. Here are some activities where you could begin:

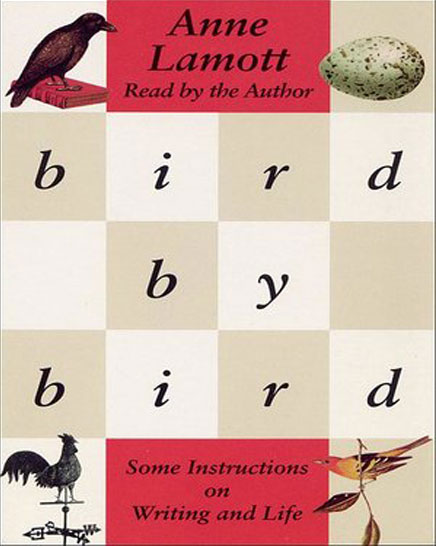

Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Yesterday I ran out the door and left my cell phone charging on its stand. By the time I realized this, it was too late to turn back. Suddenly cut off from the world of connection, I was at first upset and then had a strange sense of freedom. I had no choice except to let it go. When you hold on tight, as is sometimes necessary, you do stay focused and are able to concentrate on what needs to be done. You follow a series of steps, and don’t get distracted by random thoughts. You meet the deadline. But what do you miss? When you let go, a creative empty zone may appear, allowing space for the new. The temporary hole left by my absent cellphone generated some new thoughts, and I had to find pen & paper so I could begin to write this post. As an artist, what might you let go of, in order to allow energy and space for the new? Where are you investing too much effort, with little or no return? Maybe you’ve been a volunteer in an organization, and it’s time to let new people take over. Perhaps you keep getting rejected from a certain kind of opportunity. Instead of licking your wounds, maybe it’s time to open up new possibilities, new ways of thinking about your life and work. When you let go, it doesn’t have to be forever. You can put something on pause, you can take a break, step back and see what it might be like without that item on your agenda. The art world is constantly transforming itself, and you can do the same. How could you explore new ways of being an artist in the world? Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Artists, writers, composers and other creatives often tell me about their doubts. They wonder if their art is good enough, if they are on the right path, if they will eventually succeed. My best advice is to keep doing the work. When you are outside the creative process, your doubts and fears can overwhelm you. It is only from the inside, when you are actually writing or composing or making art, that you find the necessary confidence to keep going. If you’re discouraged about your progress in the art world, let your art-making remind you of what really matters. If you’re overwhelmed with challenges in your personal life, let your art-making center you. If you’re in doubt about your own work, remind yourself of its value by making more of it. So many artists grew up in a family of doubters. Studying art or music isn’t practical, they told you; you can do it as a hobby after you get a real job. Artists who manage to pursue an art career in spite of such advice still hear those voices. Continuing to make art is the best way to silence them. It has never been easy to sustain a life as an artist. But if you have chosen to do so, nurture yourself by honoring the art-making process. When your life is complicated, getting back into the studio will simplify it. Building your confidence is an incremental process, so find time every day to work on your art. If it has been a long dry spell, take baby steps. Ten or twenty minutes at first, then an hour, then an afternoon. Don’t judge those early results too harshly. Just let yourself get back to it. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards If there’s an art fair in your area, take the time to visit. You’ll get a great overview of what’s happening in fine art galleries. Remember, an art fair is different from an art festival, where artists sell their work directly to the public. At an art fair galleries showcase and sell the works of artists they represent. Usually an art fair lasts several days, and includes 50-100 galleries from across a wide geographical range. It’s easy to get overwhelmed! You might just wander around in a daze, especially if it’s your first time. A good way to benefit from your visit is to think about your goals, and make a plan. Go to the fair’s website, where the participating galleries are listed, and pick 10-20 you want to see. They might be galleries you’ve heard about, or ones where you might seek representation, or galleries from far away that you’d never get to see in person. These are the anchors for your visit. As you follow your plan, feel free to explore other galleries that catch your eye. The anchors just give you a structure to follow so that you don’t miss your favorites in the chaos around you. Notice trends, and pay attention to prices. Take your business cards, but don’t assume that anyone wants to hear about your own art. Remember, galleries pay high fees to exhibit and sell the work of their artists. The best ones welcome all visitors and are open to having a conversation with you. Ask questions about the artists they show. Open-ended questions like “tell me about the artist” will get you started. Be sure to ask how they discover artists. Their answers will help you plan the next steps in your own career. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards In her well-known book on writing, Anne Lamott recalls how her 10-year-old brother was struggling with a huge school project on birds. Overwhelmed and discouraged, he went to their father for help. His advice? Take it “bird by bird.” Do one thing at a time. This is useful wisdom for visual artists. Creative people tend to see everything as a whole. You get the big picture quickly, but have difficulty when it’s time to tackle individual tasks. They all seem to blend together. An artist recently told me how this feels: “everything ricochets off everything else, so it’s impossible to know where to start!” She needed a job, and a new place to live, and a new website, and a better studio, and on it went. With the whole aviary flying around in her head, she couldn’t see any one bird’s distinct color and plumage. When you’re facing many challenges that are related and seem equally important, you need to get them out of your mental aviary and onto a piece of paper, either described in a list or drawn as a mind map. The key is to isolate related items from each other so you can think about them one at a time. The process of creating your list or map can have a remarkably calming effect. Then, concentrating on one issue at a time, identify the first three action steps that would help you begin to move forward. As you do this, the jumble starts to arrange itself. You knew these items were related, but now you discover a natural sequence of actions that will sort them out in a useful way. Try this method when you’re stuck, and let me know how it works! Mary Edwards, Ph.D

Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Artists wonder, should I put prices on my website? This opens the proverbial can of worms. When you ask, more questions squirm out. First, what is your selling strategy? You need to decide, since some choices conflict with others. If you’re seeking gallery representation, don’t put prices on your website. Most galleries see this as an amateur move, thinking that you intend to compete with or undermine their efforts. Instead, put a note on your contact page that explains how to reach you for price information. Should prices on your website be clearly visible? YES. Whether you’re selling originals, prints, workshops, art tours, or any other product, be clear about the cost. When you make people search, they think you’re hiding something, or that your prices will be too high. Be transparent. Should you give people lots of choices? NO. Photographers (and other artists selling prints) seem to think that people want an infinite variety of images, available in different sizes and formats. This gives people too many decisions to make, and they get overwhelmed. Have a shop with a curated selection of works, with limited choices in size and format. Then give step-by-step instructions so that it's quick and easy to buy. Should you sell through an online gallery? Maybe. There are now so many possibilities. You can submit your work to a juried online gallery, sell through a home décor company, or sign up for a website hosting service that also sells artists’ work. Study each option carefully, and ask for sales data from the artists showing there. Don’t forget, you’ll still be responsible for driving people to your gallery through online activity, including social media. So, don’t be afraid to open that can of worms. Just take your time examining what comes out. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards |

Mary's BlogAs an artist coach, I bring a unique combination of business knowledge, art world experience, and professional coaching skill to my practice. |