In 2006 Daniel Pink predicted that the future would belong to creative people, especially those who were able to combine the two hemispheres of the brain into “a whole new mind.” While he did not anticipate our current crisis, he understood that artists could lead us through times of great uncertainty. No one knows where the art world is headed right now, so it is time to create a new one. Artists are in the best position to do this because they are able to form images in the mind of what doesn’t yet exist. When you imagine a work of art, you find new relationships among familiar things. You make a collage out of antique wallpaper found in thrift shops; you photoshop images from many places into a new landscape; you sculpt the human body in the form of a vessel. These visual metaphors help you imagine and then create something new. An artist’s mind is intuitive rather than logical, synthetic rather than analytical. You experiment with materials and process just because they interest you. You don’t need to know the end result because you enjoy the process of discovery. You are not tied to what has gone before because you can visualize an alternative reality. What would happen if artists used these right brained strengths to build an art world that supported and sustained creative people? An art world that served the needs of artists and art lovers, collectors and critics, that welcomed the participation of broad and diverse audiences? What would this new reality look and feel like? Start small. Think about your own art practice and then about your local and regional art community. What could be different? What would be better? How do we begin? ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In my last blog post I talked about an artist’s vision: what your art is all about, why it matters, how it lives out in the world. If you intend to market and sell your art, this is your first step. You start with your personal vision, as this painter did: “I paint to celebrate daily life, to illuminate the ordinary, to shape the day.” In order to create a business, you first need to think about your customers. Entrepreneurs, who are the artists of the business world, develop what is called a “customer profile.” A profile defines the demographic characteristics of the people who might buy your art (their age, gender, income level, etc.). Your customers are the audience for your art, your fans and followers, your people. You may not have a lot of detailed information about them, but take a look at what you do know. Who has recently bought your work (or would buy it if they could)? Do they tend to be older, younger, rural, urban? What do they have in common? This information will help you figure out the next step: your marketing strategy. How will your work become visible to your audience? Where will they find it? How will they learn about you? The more you know about your potential customers, the easier it is to figure out how and where they buy art. Then you’ll need to set up some simple measurements. Your art career is like a road trip, where measurements are signposts to keep you on track. This is especially important when you are stuck. A good measurement system puts you in motion again. Follow these first steps in order to create a business plan. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Please note: I recently published a longer version of this article, “An Artist Should Think Like an Entrepreneur,” in www.callforentries.com. This well-curated site lists open calls for artists and photographers. Take a look, you can join for free!  Artists are beginning to realize that their own unique vision can be a source of inspiration to others during difficult times. A local artist/teacher, Janet Jacobs, recently sent me a link to her online workshop, “Sketchbook as a Place of Solace.” The title says it all. Your own vision is embedded in the art you create. You may rarely talk about it, since the art itself expresses what you want to say. Yet it can be helpful to articulate what your art is all about. Perhaps you offer an alternate reality, as the sculptor Phyllis Thelen does: “Through my art, people may escape to serene places of the planet and the mind, and take peace and pleasure from time spent there.” Your intentions may be more explicit. The jewelry designer Leslie Lawton describes her vision: “I want to empower women to choose to be visible, to make an authentic personal statement.” Your unique vision may grow out of your choice of materials. The fiber artist Carol Durham works in gut (pig casings), a material she uses because it is “not easy but challenging, as it gives me the ability to make uncommon three dimensional forms.” Or perhaps your materials and process open up the world of art to a wider audience. The artist Nancy Nichols teaches others how to paint with coffee because it takes the fear out of the process of learning to paint. If you haven’t yet articulated your own vision, think about how people respond to your work. What do they notice? How does it make them feel? How does your vision expand their world? Whether you are a portrait painter or sculptor, a photographer or mixed media artist, a graphic designer or comic book artist, think about why your art matters. ~ Mary

Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In this moment it is hard to find the inspiration to move forward with your art practice. But think of it this way: your creativity is a source of positive energy you can use to shine your light during dark times. If you are an emerging artist, there are many ways to move forward. You can develop what is called a “coherent body of work.” You can increase your efforts to become visible online, since that’s where the art world is headed. You can learn new skills and plan for the future. Try to make progress on any of these fronts. Set simple goals that can be easily measured. Focus on process, rather than results. For example, “spend three hours a day painting in the studio” is a goal describing your effort. Some days you will feel satisfied, and at other times you’ll be staring at the canvas. Eventually you’ll see results. You can also establish goals for becoming visible online. If you already have a website, you might want to add your latest work or update your “about” page. If you’re not ready for a website, choose another way to share your work online. Instagram offers a good place to start, but if you’re allergic to social media look for something else. Join your local art center. Even if they aren’t open yet, many offer virtual exhibitions and showcase members online. Another positive goal is to learn something. There are more workshops available online than ever before, so choose one and get started. If you think you’ll want to go to an artist residency in 2021/22, start now by researching programs that appeal to you. Art careers are built out of tiny incremental steps. Hope and plan for a better future, but get ready now. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  Everything in the art world is shifting. The most obvious trend is the move toward a virtual marketplace for showing and selling art. This has been happening gradually, but now we have new evidence that collectors will pay top prices for art they purchase online. Recently Frieze, the first major art fair in New York to happen virtually, reported strong “attendance” and sales. This is just what is happening at the top. Galleries are also moving exhibitions online, artist/ teachers are offering classes on Zoom, everyone is adapting to an online marketplace. Yet I worry about what may get lost in this process. When all of our information comes from screens our senses are limited to sight and hearing. We are cut off from the other senses: touch, taste, and smell. Together the five senses provide information that is crucial for artists. They are the source of intuition, a way of knowing that is just as powerful as logic. Intuition is often described as a feeling, a “sixth sense” or “gut reaction,” a speeded up understanding that skips over cognitive processes yet still arrives at an accurate perception. For artists, much of your knowledge comes from intuition. The flat screen flattens our experience because we miss all the sensory information that deepens our connection to the world. Think of the difference between the weather prediction on your telephone vs. the actual weather. “Partly cloudy, 58 degrees” may be true, yet when you go outside you feel the wind, see the changing shapes of the clouds, and enjoy brief rays of the sun. So, my advice? Adapt to the virtual world as best you can, but never forget that the real world is the source of your art and inspiration. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In my last blog post I talked about what happens when you decide NOT to do a long-planned project. I suggested that something else might open up in the space it used to occupy. This can happen naturally, but sometimes artists need to tease out the new. How do you do this? First, follow the advice of Marie Kondo, the Japanese organizational expert. She created an international business by helping people get rid of possessions that no longer “spark joy.” Her method is odd but effective: hold each item in your hands, acknowledge the need it satisfied, and then say good-bye. If you do this with the project you’re about to abandon, you’ll be clearing space for something new. As you think about the project, identify what it meant to you. Whether half realized or barely begun, at one time your project expressed your values and needs. It might have been a new art series, or a way to earn income, or a way to give back to your community, or perhaps all of the above As you say good-bye to the project, ask yourself what was missing. Why didn’t it spark joy in you? As time passes, it may seem that nothing new will appear. Remember what nature teaches us about the creative process. In a dry season, many plants that are fed by underground streams look dead. Their branches are brown, without any signs of life. Yet slowly small green leaves begin to appear, and eventually there will be flowers. I always say that artists are like perennial plants. Your deep roots of creativity are alive, even in the darkest Winter. Give your new vision the time and space and effort it requires, and then look for the first signs of growth. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  The current global crisis makes us focus on what is happening “out there.” It is important to be a good citizen, to stay informed and find ways to help others. Yet it is also a time for reflection and learning. By looking inward we allow ourselves to grow. As you experience dramatic differences or subtle shifts in your world, notice the positive and negative effects on you. For example, is having more time making you more patient? Are you more relaxed because your days have fewer pressures? If the people around you are driving you crazy, have you found a way to carve out alone time? Are you able to tell your loved ones what you need? Whatever your circumstances, use this time to discover the real priorities in your life as an artist. Look at the commitments that used to fill your days, and no longer do. What purpose did they serve? What do you really miss? Think about the big projects that never seemed to get done, or even started, because you didn’t have time. Maybe you wanted to create a portfolio of images for submission, or learn how to build your Instagram following, or research galleries that would be right for you. If you are still avoiding that project, even though you now have time to do it, try to understand what’s going on. First, spend a day on the project you’re avoiding. Give it a fair chance to recapture your attention. Then make a decision: is it time to recommit or let this one go? If you recommit, chunk it down into manageable parts, and work on it an hour a day. Letting it go might be even more empowering. You may find your real priority in the space that opens up. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In a recent podcast Anne Lamott was asked what writers should write about in the midst of our current crisis. I loved her answer: “write what you would like to come across.” I think this is also good advice for visual artists. Lamott is telling us to remember our own needs as we think about our creative practice. There is only so much time you can spend in front of screens, whether you’re following the news or connecting with loved ones. At some point it is time to make art again. Why is this so important? Creativity is a natural resource like the energy of the sun--it nurtures you. When the whole world is out of kilter, your art keeps you in touch with the core of yourself. If you cannot leave the house, clear the dining room table or a space in the kitchen. Start by organizing your materials. You need to be able to see and touch your art. Perhaps you will decide to learn a new technique, or experiment with color or clay. Work on something that gives you pleasure. Make a simple plan, and then identify your first steps. You don’t need hours or days in the studio. If you think you don’t have time, or even if you have too much time, start by spending 30 minutes a day making art. Sketch out ideas you will implement later. Gradually increase the time when it feels right. You can share images with friends and followers, but you don’t have to. This art making is just for you. Build art back into your life so that it sustains you through difficult times. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  No matter where you live you’re being asked to cope with a whole new set of circumstances right now. I’m in Northern California and have been in “lockdown” for nine days, with no end in sight. My blog post today is about how to find and use your strengths to help yourself and others. Especially when you feel stressed or uncertain, remember what you have to offer. Try to replace complaints with gratitude. Think about what is still positive in your life. Artists have special gifts, often called “right-brain” strengths. These include your imagination, the ability to see the Big Picture while others are focused on small details. Artists are also intuitive, with the kind of insight that isn’t based on logic but is still powerful. You have the flexibility and imagination to navigate difficult times, and to help others to do so. Remember that under stress we all become more like our core selves, not less. If you are an introvert, you won’t mind time alone but will still need to connect in other ways. If you’re more social, you might be feeling a sense of loss that more screen time simply doesn’t replace. Also remember that people handle stress in different ways. Be patient with others, including friends and family as well as strangers. Try to identify your personal strengths. Think about your own past. Remember the difficult times you thought would never end. You may have suffered a personal or professional crisis, the loss of a loved one, the loss of a dream. Or perhaps you faced an exciting challenge that seemed beyond your ability. When you look back, what were the strengths that got you through? Whatever worked then, do it now. Find your strengths and share them with others. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In my coaching practice I’ve identified 8 abilities that are key to an artist’s development. Take a moment and think about how you are doing on each one:

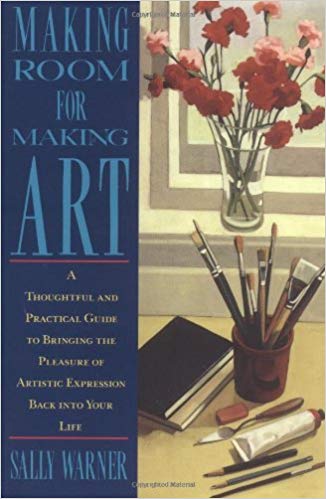

The first two abilities are the foundation for your art practice. When you ask, “where am I now?” you see the realities of your life as an artist. Don’t worry about where you expected to be by now, just acknowledge where you are. Begin with your art practice, rather than your resume. Are you making art every day or almost every day? Are you connected to an art community? Do you pay attention to opportunities in your field? When people ask, “what do you do?” do you answer, “I am an artist” without apology? The next area is challenging in a different way. Try to imagine what success would look and feel like for you. You may be most interested in developing a coherent body of work. Or you would like to become more visible in your community. If you’re an established artist, you might imagine your first solo museum show. By knowing where you are now and then imagining what success would look and feel like, you discover your authentic path. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  Here is one of my favorite books about how to maintain an authentic life as an artist. Sally Warner, an artist herself, writes to those who have lost their way and are trying to find a path back to a creative life. Every artist I know feels lost at some point. You may feel overwhelmed by the noisy demands of social media. You may have recently gotten rejected by everything you’ve applied for. Or you’re lost in the confusion and stress of your own life, where too many people want a piece of you. What can you do? In a chapter called “Strengthening Your Creative Resolve” Warner describes ten qualities that will help you continue to make art. These include endurance, perseverance, and flexibility, but her most original recommendation is for artists to value their own creativity. For me, valuing your creativity means that you trust yourself and your talent. You are patient with yourself when you encounter obstacles, you celebrate your smallest successes, and you silence the inner voice who says that you’re not good enough. You strengthen your creative resolve by allowing the art-making process itself to heal you and move you forward. You go back into the studio (or wherever you make art) and spend just a little more time every day reconnecting with your art practice. Even if you don’t have a new idea yet, honor your creativity by being present in your own art space. Touch your materials, make a sketch or look at your portfolio, write a few words or read an inspiring chapter in a book like Sally Warner’s. Gradually your art will make room for itself. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  We’ve been talking about the challenges of the new year and new decade. You may have big goals in mind, or even small but difficult ones. You have gotten organized, you’re being strategic, but you still aren’t quite there yet. Maybe it is time to ask for help. There are many kinds of art professionals who can help you with your career, including agents, curators, art consultants, and coaches. Today let’s talk about art coaches, people who help you make progress in your art practice or career. Take your time in finding a coach who is right for you. Look at their websites, read testimonials, and check out their background and expertise. Reputable coaches are certified by a professional organization and offer a free consultation so that you can get a feel for their style and personality. A good coach will help you figure out what you want to achieve. They will recommend practical strategies. They listen to you carefully so that they hear what you are saying and struggling to say. A good coach is your partner and champion, someone who believes in you. A good coach will give you a structured process to follow. Typically you’ll begin by defining your goals, identifying the obstacles that might get in your way, and planning specific action steps for you to follow. The coaching process offers what is called a “structure of accountability.” This means that you are motivated to take action steps because you have an objective partner who cares about your progress. Interview several coaches before you decide. Ask yourself, who do I trust? Who is best qualified to help me? Keep looking until you find the coach who is right for you. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  We’ve been talking about the challenges of this new year and new decade. My last blog post was about being strategic in your art practice, so that you spend more time on what matters most to you. The first step for many artists is getting organized. How do you organize your time, your studio, your paperwork—how do you organize yourself? Most systems of organization are not “artist-friendly.” They are linear, like an Excel spreadsheet, or a checklist of to-do items. Such left brain systems do not capture your imagination or release your energy. These systems are often invisible--they get lost somewhere in your desk or on your computer. Out of sight, out of mind. Artists are visual people, so you need to organize yourself visually. Find images and objects that represent your intentions. If you’re trying to plan a career path, draw a map with signposts along the way. If you want to get on top of paperwork, find or create a beautiful container where you collect all the bits and pieces of paper that you need to keep. If you want to organize your time, use a big paper calendar and block out your days in different colors or shapes. Getting organized also means making choices and setting boundaries. You begin by putting your most important work right in front of you. You shape your days around your priorities. You might have to let go of some activities and even some people. You won’t always be flexible and available to others. Since getting organized means doing more of what matters to you, you begin to say NO to less important demands. What is your first step in getting organized? ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  Facing the New Year can be both exciting and daunting, and facing a new decade only increases the pressure. In my last blog post I suggested that you begin by creating a mantra to guide your thoughts and actions, because a simple word or phrase keeps you on track. A good mantra for artists who want to grow their practice is “be strategic.” What does it mean to be strategic in your art career? First, think about what really matters to you. Maybe it is making time to create a new body of work, or making an effort to reach out to others who can help you advance. Perhaps this is the year when you will seek advice about gallery representation, or build your presence on social media. Pick just one thing to work on, for now, and “be strategic” about it. Being strategic means that you are conscious of what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. You don’t worry that you cannot control the outcome, you just go ahead and act. For example, if this is the year when you want to reach out to others, you reach out to someone every day. If you decide to develop a new body of work, then you increase your hours in the studio, and say no to less important activities. Being strategic means that you shape your days around your priorities. Even If you’re not a morning person, you start the day with what matters most. No matter how many demands and distractions come at you, each day you do at least one strategic thing. In this way you gradually build momentum, so that your actions become natural and new ideas start to flow. Remember, as an artist you are a visual person. Try to find an image that represents your strategy, and keep it visible wherever you are working. Let me know what you discover. ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  This is the time of year when many of us look back at what we have accomplished and think about what the new year will bring. Most of what happened for me in 2019 grew out of commitments made before the year began. I ended up writing a lot. In addition to this blog, I made progress on my book, Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People. I also created a number of long articles for the online newsletter CallforEntries.com, including a series on How to Approach a Gallery. So what will 2020 bring for you? Sometimes New Year’s resolutions are so specific that they set you up for failure. You really cannot control the activities of others, especially people in the random and chaotic Big Art World. So you might want to take a more fluid approach, where you commit to making gradual changes in areas that matter to you. Ask yourself these two questions:

In order to make progress as an artist, you need to change subtle patterns in how you use your time, what you pay attention to, even what you think about. Your creativity is embedded in the rest of your life, so think broadly about the two questions. Always start with the positive--what you want to do MORE OF. As you shift your energy, the LESS OF will become obvious. Then turn your intentions into a simple mantra, a word or phrase that will guide your behavior. For example, if you’re trying to lose weight, your mantra might be “drink more water.” If you need to free your mind for your own creative work, a good mantra would be “take long walks.” If you’re trying to improve your presence on Instagram, try the mantra “take better pictures.” My own mantra for 2019 was “write every day.” Specific goals and measurement systems are useful, but a mantra stays with you because it’s easy to remember. It can speak to you in a whisper or a shout, but it’s always on your mind. What is your mantra for 2020? ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  In my research and my own work with artists I’ve discovered 10 behaviors that make a difference in an artist’s career. Take the quiz below to see how you are doing. Be honest as you answer the questions! Then pick one or two areas to work on, and see what happens. If you would like to know more, feel free to contact me. Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards Checklist for a Successful Art Career How are you doing? Think about your current behavior, and rate yourself 1 (Rarely) to 5 (Always).

When you write about your art you leave the world of images and enter the world of words. Going from the visual to the verbal plane is a profound shift in perspective. When you try to write about your art, something happens. You procrastinate because it feels awkward. You fear that words will destroy the fragile integrity of your work, or reduce it to something less than it is. Try to remember that making art and writing about it are profoundly different ways of communicating what you know. One does not replace or destroy the other. When you write well about your art, you open a door to all the people who live in the world of words. Writing, like art-making, is a creative process that you can learn. The process develops in stages, where one stage leads to the next.

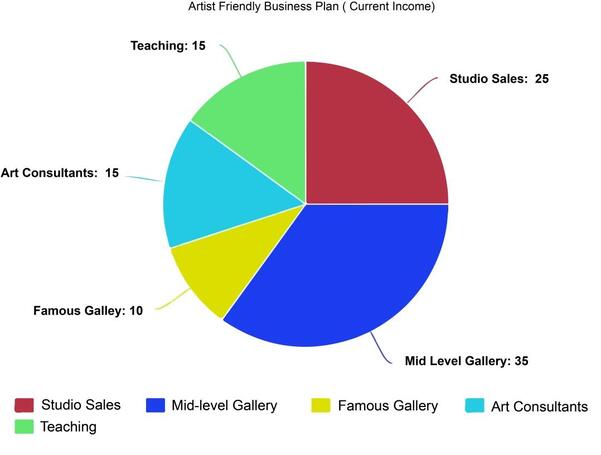

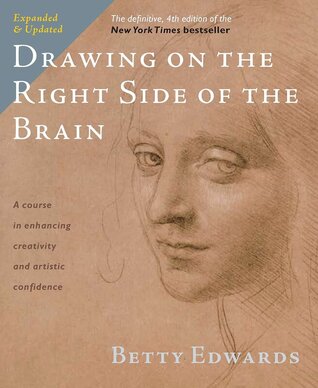

Create good conditions Pay special attention to your setting, materials and process. Find an appealing place to write. It might be a corner in your apartment or a table at your favorite café. Choose a place that you like to be. Then think about writing materials. If your brain shuts down when your fingers hit the keyboard, consider using an old-fashioned pen and notebook or a stick of charcoal and a sketchbook. These implements create a physical connection between your hand and your brain. Make your writing process portable. Even if you start at a keyboard, always have writing materials with you. Discover what you want to say To begin, don’t stare at a blank screen or empty notebook. Look at your art. First, look through your bodies of work. Review images as well as actual works, and think about what they have in common. Write down a few words or phrases that capture your intentions. Then pay attention to individual works of art. Choose one or two of your favorites, and notice the details. How do they convey meaning? You might note your use of color or composition or choice of materials. Again, write down a few details that are worth noting. Create that messy first draft Your goal is to write a page or less about your art. Think of it as a new artist statement, written in the first person. Your page will be messy and long because you won’t find the right words until you write down a lot of almost-right ones. Work for an hour or so, and then stop. Put your writing aside. Take a walk or do something else that keeps you in motion. Your brain will keep working, searching for better words. This is why you have a mobile writing process, so you can easily keep track of new thoughts as they occur. Revise, edit, and polish When you have a first draft that makes sense to you, print it. Your words look different on the screen vs. the printed page. Revise again. Editing at this stage is a pruning process, where you cut off the dead parts to help the living plant grow. Now you can ask for feedback from friends and professionals. Ask them to tell you if your ideas are clear, or if there are awkward or confusing places. Incorporate useful suggestions. You learn to write by writing, just as you learn to play the violin by playing it. Honor the stages of this creative process, and you’ll gradually become a better writer. * Please note: I recently published a longer version of this article in the October 2019 Newsletter for www.callforentries.com. This is a well-curated national site which lists open calls for artists and photographers. Please take a look, artists can join for free! ~ Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Betty Edwards’ classic book, has sold almost three million copies and is essential reading for artists and other creative people. She teaches us that in order to learn how to draw, first we have to learn how to see. This requires a radical shift in perspective, as we let go of the “left brain” world of words and thoughts and numbers, and shift to a purely visual plane. The book is a powerful reminder that our brains operate in different modes that we use for different purposes. Living in a purely visual world comes naturally to artists. You get uncomfortable when you have to come back to the world of words. When you need to talk and write about your art or do other career tasks, you are making a profound shift. Pay attention to this transition. If you’ve spent the whole morning in the studio, happily making art, don’t get on the computer right away, even if you just plan to do a simple task. Take a walk, read a book, listen to music, play with the dog. Give your brain the time it needs to make a transition to a different way of operating. Then spend an hour or two doing all those left brain tasks. Answer emails, update your website, enter that juried show, draft the proposal. All of these activities use the same part of your brain, so it will be easier to do them together. When you’re done, take another break before you re-enter your creative space. Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  How do you price your work, especially at the beginning of your career? Artists often look for a shortcut, a simple way to figure out pricing, like adding up the cost of materials or charging so much per square inch or counting the number of hours it took to create the work. These methods don’t work because they ignore how the art marketplace operates. It is not just your time, but your talent and experience. Think about it. A 36” by 24” oil painting might sell for $500 or $5000 or five million dollars. Your name and reputation determine your prices. In order to establish your first prices, you need to do research. Visit local galleries and art centers who show emerging artists. Find a juried group show that includes work in your medium, like traditional landscape painting or abstract art or ceramics. Choose artists whose work you admire, and note their prices. Later on you can check the websites of these artists to evaluate their background. Are their prices justified by a solid record of accomplishments? Now look at the wider art world. You can do most of your research online. Both UGallery and Zatista are juried sites that offer original art for sale. Again, find artists in your own category whose work you admire, and note their prices. You can also look at large retailers, like Crate & Barrel, who sell both prints and original art online (see “wall décor”). Compare the artists’ resumes with your own. If you are a maker of handmade goods, you can do research in the same way. Take a look at the range of prices on Etsy. Find items that are similar to your own in terms of quality of materials, originality, and skill, and see what they cost. Does your jewelry fit at the low end, in the middle, or in the higher “one-of-a-kind” market? When you are ready to establish your own prices, start with your largest and most complex work. Based on your research and your own selling history, what would a fair price be? Imagine yourself walking away with a check in that amount. Are you smiling or puzzled? Do you think you’ve received fair compensation for your effort? Then price medium-sized and smaller works accordingly. You might want to provide a range within each category, so that you can adjust prices for works that are more or less complex. Your goal is to establish prices that are credible in the current art marketplace. The next time a buyer asks “how much is that?” you will have a confident reply because you know the value of your work. Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  Your art career might seem like a pile of unrelated puzzle pieces. You are trying to do a lot of different things: make a plan, be strategic, use social media to become visible, develop a coherent body of work. But when will the whole picture become clear? Entrepreneurs face the same challenge, and you can learn from their experience. Artists and entrepreneurs have a lot in common. You both struggle to make an idea happen. Entrepreneurs have to identify potential customers, just as you need to find your audience. You both need to present your work in a clear and compelling way. Successful entrepreneurs have an attitude that can be inspiring to artists. They approach their work with an open mind and a spirit of experimentation. They take risks, they invest in themselves, they get advice from experts, and most of all, they learn from their failures. Biographies of entrepreneurs always tell stories of their early efforts: an idea that proved impractical, an experiment that didn’t work hundreds of times before it succeeded. Artists embrace this spirit when they are making art, but somehow forget to apply the same attitude to their art career. You try something once, and if it doesn’t work you give up and blame yourself for your failure. Entrepreneurs teach us to embrace two ways of being in the world. First, you organize and plan. You set goals and measure your progress. You ask for advice and follow it. These activities start to fill in the outlines of your jigsaw puzzle. They help you see the larger picture of what is possible. And then you let go, and open yourself up to the random gifts of the universe. Again and again entrepreneurs tell us about the opportunity “that came out of nowhere,” the accidental meeting with an investor, the sudden insight about a new approach. These seemingly random happenings are the result of all the hard work that went before. Think of your art career as a jigsaw puzzle, where your job is to put enough pieces in place so that the outline of the whole picture begins to take shape. That’s when the magic happens. Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards In my last post we saw that artists often face a dilemma. Your creative process is one way of perceiving the world, while managing a career requires a whole different set of skills. When you are making art and then trying to promote it, you go back and forth, again and again, using opposite parts of your brain. No wonder you get exhausted and discouraged! So what can you do? You can use your strengths as an artist to transform “left brain” career skills into artist-friendly tools and techniques. Here’s an example of how this works. An abstract painter was trying to grow her business. As a mid-career artist she had already been successful in finding gallery representation, and was also using a number of other strategies to sell her work. Her bookkeeper kept track of her sales, providing monthly reports on Excel spreadsheets. This information, so vitally important to her business, was presented in a detailed, logical, sequential, linear format. When she looked at the documents they didn’t mean anything to her, so she kept forgetting them. When this data was transformed into an artist-friendly format, the artist suddenly realized what those excel spreadsheets were trying to tell her. She immediately understood how to grow her business. “The famous gallery isn’t really doing much for me! I’ll talk to Joyce (gallery director) to see what’s happening there. Maybe another mid-level gallery would be better for me.” Later on she noticed: “My studio sales are a larger part of my business than I thought! I’ll schedule more regular events in the studio.” Her pie chart was a visual shorthand that communicated directly to her artist brain. In another example, an emerging artist went to a workshop and developed a business plan for her art career. She spent a lot of time and energy on the plan, and was very excited about it. She then kept it hidden away in a file on her computer. Months later she was surprised and disappointed that nothing was happening, and blamed herself for being lazy. The artist’s good ideas disappeared because they were no longer real to her. She needed to figure out how to translate her plan into an artist-friendly format so that she could see it, touch it, and feel it. She constructed a topographical map out of papier-mâché, showing the sequence of steps she wanted to take. She included a small maquette of an urban gallery space, since that was one of her goals, plus a tiny version of her art placed in a sculpture garden. By creating a version of her plan that she could see and touch and feel, the artist brought her business plan back to life. She then was able to make it happen.

If these suggestions seem a little odd, remember that you are simply replicating what you do as an artist, as a maker. When you make art you give form to an idea or a feeling. You capture an impression in clay or on canvas, or in a photograph. You can use this same ability to learn the career skills that will help grow your practice. Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  A sculptor is working in his studio, completing a large scale piece of public art. He gets so lost in the process that he forgets the 5:00 p.m. deadline to enter this work in a national juried competition.  An abstract painter is at home at her desk, checking off items on her family’s to-do-list: make a dentist appointment for her son, pick up the dry cleaning, balance the checkbook. She wonders why she has no energy to go into her studio and paint.  A fashion designer is sketching in her notebook, pleased at the look of the new dress she has created. She can envision her model walking down the runway at New York Fashion Week. But when the designer sits down at her sewing machine, she has difficulty following the detailed instructions about how to get a zipper to lie flat on the delicate fabric. What is going on here? Why does the sculptor forget his most important goal? Why does the painter get stuck in routine tasks, when all she really cares about is making art? Why is it easy for the fashion designer to imagine her creation walking down the runway, but difficult for her to execute the details of the design? Are any of these dilemmas familiar to you? Do you recognize your own struggles as an artist?

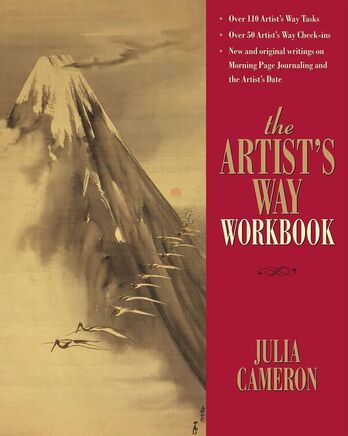

If you do, you may realize that the source of these dilemmas is not “out there” in the challenging demands of the art world, but right inside your brain. Think about your own experience as an artist. When making art you are using right brain skills and processes. You are visual, intuitive, spontaneous, and you may stay in that mode for hours or even days at a time. You experience the world in a holistic way; your imagination runs freely as you make something new. This is how the creative process works while you are making art. But when you are working on your career, suddenly all of the demands are for a different kind of thinking. You must pay attention to deadlines, follow detailed instructions for entering your work in exhibitions, develop and follow a business plan to get where you want to go. You have to become skilled at talking about your work to collectors and the public. You need to write about your work so that others can understand it. Unfortunately, all of these critical career skills are housed in the left side of your brain. Do not despair. My work with artists has revealed a simple and elegant answer to this dilemma. When you translate left brain concepts into visual images or spatial objects, your right brain understands what they mean. You are then able to see how such ideas apply to your own career. You are able to use your strengths as an artist to learn skills that seem foreign to you. In my next blog post I will show you how this process works! Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists “Left Brain Skills for Right Brained People” Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  It’s Summer and you may be taking it easy. But if you’re looking for inspiration, consider the Workbook for Julia Cameron’s classic book, The Artist’s Way. The workbook is organized into 12 chapters full of wonderful ideas and exercises designed to help you recover the basic building blocks of a creative life. Cameron assumes that creativity is our birthright, whether or not we define ourselves as artists. Her workbook shows you how to bring your creative self back to life. Here are three of my favorite exercises: 1. “Describe five traits you liked in yourself as a child. Next, write a little bit about why each one appeals to you.” 2. “List five childhood accomplishments (got straight A’s in seventh grade, trained the dog, punched out the class bully, short-sheeted the priest’s bed). Reflect below on your memories of those experiences of success. And a treat: List five favorite childhood foods. Buy yourself one of them this week. Yes, Jell-O with bananas is okay.” 3. “Make a list of friends who nurture you—that’s nurture (give you a sense of your own competency and possibility), not enable (give you the message that you will never get it straight without their help). There is a big difference between being helped and being treated as though we are helpless. Describe which of these friends’ traits particularly serve you well.” (From “Week Three: Recovering a Sense of Power” The Artist’s Way Workbook, by Julia Cameron) I recommend these exercises because many artists are hard on themselves when they are not making progress. You tend to judge yourself harshly, when what you need is loving care. The first two exercises help you go back to your childhood in a positive frame of mind. You identify some of your core strengths, qualities in yourself that you can recover if you remember them. In the third exercise you think about the people in your life. When you identify the friends who nurture you, you will gradually make more space for them. And then you’ll have less tolerance (and time) for people who do not support your growth. Enjoy your Summer! Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists www.coachingforartists.com coaching@coachingforartists.com Instagram: coachingforartists.maryedwards  You just received an email from a New York gallery, saying that they saw your work online and loved it, and would like to offer you a solo show in a “real New York Gallery.” WOW, you think, you’ve been discovered at last! You respond right away, spend quite a bit of time sending high resolution images and other information they request. You start telling your friends about your New York gallery. After several enthusiastic emails, they casually mention that “your share” of the cost of the show will be $3000. This number should stop you in your tracks, because you really do know better. But you’ve been seduced by their flattery, already invested time and effort to meet their requirements, and told all your friends about this great opportunity. You seriously consider sending that check because they make it seem like it’s just the next step in a normal process. That’s how pay-to-play galleries operate. They get your attention, flatter your ego, make you invest your time, and then ask for the money. Artists need to learn how to evaluate these scams. When you first receive such a letter or email, slow down. Do not respond at all until you learn more. First check to see if the gallery has been listed as a “pay-to-play” gallery. Artbusiness.com has a reliable list, organized by location. You can also type the name of the gallery and the words “experience with” into any search engine. People who have had bad experiences don’t keep it a secret. So, what’s wrong with a pay-to-play gallery? Everything! They don’t add strength to your resume, you are unlikely to sell any work, and you may be associated with artists of doubtful quality. Your money would be better invested in a new website or marketing campaign. Since a legitimate gallery needs to sell your work in order to earn their commission, they cultivate a base of established collectors.. Your work might also be shown at art fairs or other high-profile events. A pay-to-play gallery does none of this, because they don’t have to. They already have your money, so they don’t invest the time and effort required to market and sell your work. You will have an actual show in a real New York gallery, because that’s what you paid for, but it is unlikely that the exhibition will generate sales or good visibility for you. If you have already been taken in by such opportunities, don’t feel bad. Many artists struggling to find gallery representation are vulnerable to these offers because they seem to present a shortcut to doing the time-consuming work it takes to create an art career. Don’t waste your time and money! Develop your own plan and follow it. Mary Mary Edwards, Ph.D www.coachingforartists.com I am a Career & Life Coach for Artists, based in the San Francisco Bay Area and working with artists nationally and internationally. If you have a question, please write to me at coaching@coachingforartists.com. You may visit my website to sign up for future blog posts or schedule a time to talk with me about your own career.  Here are the qualities to look for in a gallery contract:

Mary Edwards, Ph.D Career & Life Coach for Artists |

Mary's BlogAs an artist coach, I bring a unique combination of business knowledge, art world experience, and professional coaching skill to my practice. |